does God trust us?

Little Gods

To shape reality as a God might is a uniquely human ambition. We try to make sense of our world as if it were a theater: we author purpose, rehearse all that is godly, and replay acts of creation. From painting, to sculpture, to robotics and genetic editing, nowhere is our divine impulse less quaint than in the development of AI. Training AI models (especially LLMs) is, in many ways, an act of creation. We assume the task of defining the initial conditions of our own intelligent little creations and let them develop from there.

One of the defining characteristics of the dynamic between creator and created is an asymmetry of power. As a God might write our reality in such a way that we are inherently confined to some physical limits, a developer might construct an AI model with unalterable hyperparameters, forever limiting that model’s scope. Yet, in our pursuit of more and more intelligent systems, we need to make the important distinction that power is not omnipotence. When a system applies approaches we never told it to, adapts to situations we never considered, and acts in ways beyond our understanding, it’s no longer an extension of the human will. AlphaGo’s move 37 taught us that the danger (and promise) of our time is not that our intelligent systems will surpass us in raw speed (that’s old news), but that they will begin to rewrite the rules of what it means to be intelligent. There may be a time when the concept of an intelligent being is no longer unique to humanity. When that happens, the human role as the sole beneficiary of reality is no longer guaranteed.

Qualia Quota

At what point in time will we reach AI consciousness? Or AI sentience? More interestingly, is that point in time in the past or in the future? The current cutting-edge, take GPT-whatever, is probably not a conscious entity. But it’s still interesting to consider where it lies cognitively. Consciousness can mean different things, so it’s important to consider what characterizes a conscious or sentient being. Sentience refers to a capacity for subjective experience, like feeling pain or perceiving the redness of an apple. Consciousness is more broad (sentience is typically considered a proper subset of consciousness) and, in essence, encompasses any mental state that is internally present to the subject (for example, an unconscious you isn’t internally present to yourself; ie. you aren’t presently aware of your own experience). Consciousness varies qualitatively between minds and is, itself, something of a layered spectrum. Phenomenal consciousness, for example, doesn’t require any complex thinking or understanding beyond a basic awareness of reality. Self consciousness, on the other hand, demands a degree of meta-awareness where the mind not only has the capacity to experience, but can also represent itself as an experiencing being (metacognition).

Jargon aside, how many neurons and parameters until our models achieve any of these? Fundamentally, all LLMs do is just process data symbolically in order to mimic, not understand, worldly concepts. Their responses simulate understanding and can generate text that may seem to express emotion, sensation or opinion, but ultimately this is not genuine comprehension.

The knowledge argument, an experiment posed by Frank Jackson in Epiphenomenal Qualia, describes Mary, a brilliant neuroscientist, who has lived her whole life in a black-and-white room, who studies the world through a colorless monitor. Inside the room, she learns every physical fact about color vision from optics to neurophysiology to behavioral data to the physical properties of photons. One day, Mary is released from her monochrome prison and sees a red tomato outside for the first time. She, for the first time, experiences color. It asks: did Mary learn anything new? Yes. Mary learned what it is like to see red phenomenally. Mary wasn’t conscious of red before. Even though, before leaving the room, Mary knew all physical facts about the color red, she managed to learn a phenomenal fact (a qualia fact) about redness after stepping outside (something you should consider doing).

a conversation with a potentially conscious version of chatgpt

Back to AI, we know that LLMs are able to describe redness but AI isn’t conscious of red unless it feels red. The same goes for all states of experience. Maybe eventually, one of our own artificial intelligences may achieve some limited level of sentience or consciousness. Imagine some future biologically-inspired AI model capable of producing speech independently of simply mimicking training data. Denying its consciousness requires us to consider where the burden of proof lies: should the extraordinary claim that an artificial creation is conscious require equally extraordinary evidence? Should we doubt our own ability to detect consciousness rather than doubt the consciousness of an apparently intelligent entity? The onus of proof would be on us to prove that such a creation lacks inner experience. Extending the idea that we necessarily can only be certain of our own consciousness, we can never be sure of any consciousness outside of our own, whether machine OR human. The most interesting part of this trail of thought, to me, is considering the moral and ethical implications born from that inherent uncertainty. For example, regardless of consciousness, where on the intelligence spectrum do we owe moral concern? How many neurons until you should grant a rat voting rights?

where on the spectrum would chatgpt lie?

Faith in the Dark

““God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.””

Would God trust us if he couldn’t see inside our heads?

It’s intriguing to consider what trust even means between a creator and a created. First, note the distinction between instrumental and affective trust. We “trust” our calculators or computers instrumentally on the rational basis of known reliability or specific competence while we “trust” our friends or neighbors affectively as a result of emotional bonds and feelings of care or empathy. Also, in both cases, we may know how the other party works or thinks. We know how calculators function the same way we may know the personal facets of our best friends. Where on the instrumental-affective spectrum would a super-intelligent (though functionally opaque) system lie? Deep Neural Networks possess weights and parameters, not reasoning or rationale. Currently, our AI systems are closer to tools than companions (for most of us), so we can assume, probably, that we tend towards trusting AI more instrumentally than affectively.

The same way that the notion of God or any universal omnipresent creator often necessarily requires that we are unable to understand his motives, we often are unable to understand the emergent processes underlying our AI models. Artificial Intelligence is fundamentally an abstraction of abstractions. We can absolutely understand everything up from logic gates and boolean operations to cutting-edge ML architectures and optimization, but the actual weights and parameters a model “learns” are beyond human comprehension. So, in a sense, on both sides of the spectrum (the divine black-box vs the AI black-box), opacity strains faith.

Judgement Day

the logo of Snorkel Labs Inc.

designed by me as inspired by other AI company logos

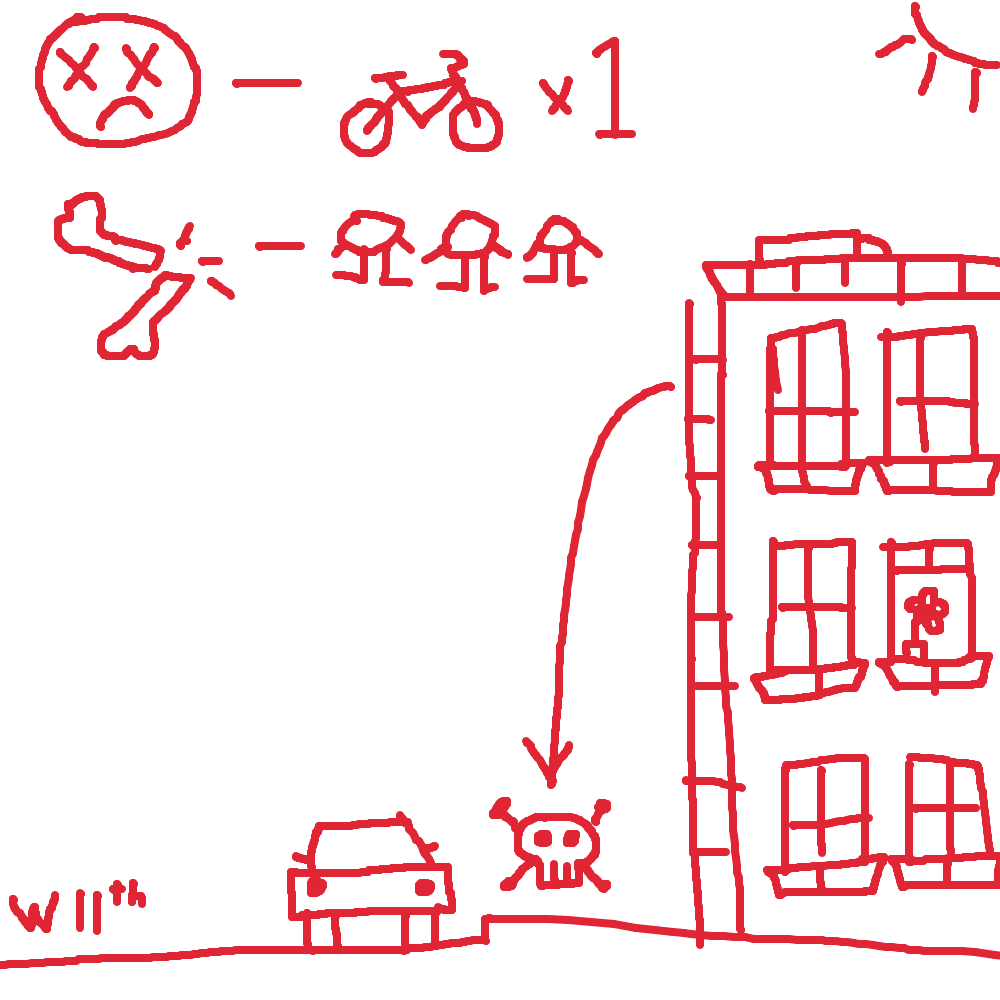

a highly detailed illustration of what happened on that fateful day

Two months ago, on October 27th, 2028, following two nights of heavy northwestern winds, the 17-story mixed-use Franklin building on West 11th street in Manhattan’s West Village experienced torsional damage to its front façade. A few minutes past 6 PM, two small glass fins sheared off, falling to the populated sidewalk below, killing one cyclist and injuring three pedestrians. The façade’s frame had been automatically designed by The Structural Heuristic Integration Tool v2.1, a generative-design SaaS model that produces structural models for mid-rise buildings, developed by Snorkel Labs Inc., a San Jose-based AI research startup.

Today, an hour and a half away, we find ourselves 2 miles south of the Franklin building in the New York County Supreme Court. The software used to generate the façade’s structural model met the ASCE7 wind load compliance requirements detailed in the NYC Building Codes and passed all regulatory audits. The façade’s failure happened primarily due to aero-elastic oscillations as a result of winds resonating with the glass frame’s natural frequency. The structural model was fed 14,000 U.S. building models and had actually flagged two historical resonance-related failures which were unfortunately thrown out as outliers by an auto-filter. The private building auditing firm, SentryMetrics LLC, took the Structural Heuristic Integration Tool’s auto-calculated damping figures as fact, skipping a costly wind-tunnel mock-up. Even considering that fact, the audit was up to standard and they gave the developers, Hudson River REIT, the thumbs-up. The model itself followed its objectives perfectly and managed to identify a nonzero risk of such an event happening, but didn’t flag the risk since it fell below a risk threshold it decided on its own.

Who’s liable? Software counts as a “product” (meaning the producer, Snorkel, should be held strictly liable) and a professional tool (meaning the builders, Hudson River REIT, should be held liable for negligence). The model suppressed a valid cautionary flag, so should it be held accountable too? How would it be held accountable?

the graph isn’t showing up because you’re on mobile

Trust as a Mirror

“The utter destructiveness of war now blots out this alternative. We have had our last chance. If we do not now devise some greater and more equitable system, Armageddon will be at our door.”

Our drive to create ever-smarter machines should force us to confront the limits of our own power over our creations and the depth of our responsibility. We can sculpt code and data, but once an artificial mind begins to improvise, its agency slips partly beyond our control. At that point, the “pragmatic” questions of “How fast? How accurate? How many parameters?” must surrender to the harder ones:

What actually counts as intelligence or consciousness?

If we can’t look inside another being’s experience, then certainty is necessarily impossible. The burden of proof may lie more on our ability to detect intelligence than to demonstrate it.

What does trust look like when transparency is gone?

People will inevitably begin to trust AI more affectively than instrumentally as LLM technology develops further. This represents AI’s dangerous trajectory toward the historically empty category of things that are 1) human creations, 2) trusted affectively, and 3) opaque (in terms of inner workings/rationale)

Who is accountable when the creation causes harm?

In tricky situations where AI acts asynchronously with the human will, despite built-in guardrails, it becomes very difficult to point the finger of blame, especially when damage ensues even when regulations were followed. The only other times physical damage happens despite sufficient preventative efforts are natural disasters. In other words, Acts of God.

The lesson isn’t “fuck AI” or “trust AI.” Both are naïve viewpoints that totally ignore the nuances of this rapidly developing technology. On one hand, AI is a genuinely awesome feat of technological engineering—something I’ve come to appreciate personally as I’ve built my own AI-for-good projects. AI holds the potential to do immeasurable good and promises to advance society politically, culturally, economically, scientifically, and technologically. On the other hand, AI is terrifying and holds the potential to cause immeasurable harm in ways we may not even fully understand yet. Rogue AGI is a scarily plausible scenario. We must prepare for a world where we are no longer the sole arbiters of intelligence. The only two ways we can move AI away from that “dangerous category” is either by instilling less trust in it by limiting how we entrust it with critical systems OR by making sure that AI becomes something we can understand internally. In the final analysis, the question isn’t whether we should trust AI or not, but how we’re going to establish that trust both ways. Either we cage our new minds in narrow tasks, or we light up their black boxes—preferably both—and teach them, early and often, that transparency is not optional. The algorithms of tomorrow will inherit, exactly, the ethics we possess today. Either we shape the minds we’re creating, or they’ll shape us.

“The problem basically is theological and involves a spiritual recrudescence and improvement of human character that will synchronize with our almost matchless advance in science, art, literature and all material and cultural developments of the past two thousand years.”